What’s Going On Behind the Mask…

Monica Baskin, PhD, SBM President

Monica Baskin, PhD

Monica Baskin, PhD

SBM President

In my last message, I encouraged you to join to Let’s Go All IN: INclusion, INnovation, INfluence. As the theme for my presidential year, I am thrilled to see how so many of our members and partners are diving right in to make a difference in our field and the larger society. I look forward to seeing, learning, and sharing more about what SBM is doing in each of these areas over the next several months.

This quarter, encouraged by the writing of Dr. Matthew Whited, I decided to embrace the idea of non-academic writing as a chance to show our vulnerability. So I have chosen to “lower my mask" and share with you a bit of introspection as I have tried to navigate my professional and personal life over the past few months.

Several who know me might describe me as strong, poised, approachable, insightful, assertive, intelligent, strategic, wise, even-tempered, and a problem-solver. In fact, I asked a few friends and colleagues to describe me in three adjectives and these were their actual words. While I am sure they were too polite to describe any of my negative attributes—and I certainly did not ask for input from my 16-year-old daughter—I suspect that most who have interacted with me in recent months see me as someone who is fairly well put together. In reality, on more days than I care to count, just under my cotton mask lurks a carefully crafted expression designed to hide the sadness, anger, frustration, anxiety, depression, and fear that has gripped me the past few months.

During this season, I have attended multiple virtual and socially distanced funerals, agonized over whether to choose all virtual, blended, or in-person school for my teen, struggled with whether my family would travel to visit my mother and in-laws who live in another state, missed communications because of the exponential increase of emails in my inbox, and attended an average of seven Zoom meetings per day. I have also managed to keep a pleasant tone as I responded to countless requests to conduct diversity trainings or speak about racism in my non-diverse circles. While I likely smiled, nodded, and laughed a time or two, the multiple pandemics of COVID-19, racism, and anti-science have depleted my physical and mental health. Like Dr. Crystal Lumpkins shared, this time has led me to a new consciousness of the challenges of multiple identities (African American, woman, wife, mother, researcher) while navigating systems plagued with bias and the need to rediscover why I do what I do.

While this season is not yet over, I want to share with you two wellness tips I have implemented to strengthen my resilience during this challenging time.

- Be Kind to Yourself. This is not the time to scold yourself for what you didn’t do or what could have been. You deserve a bit of grace. Make the time every day to do something that heals your soul and gives you energy. Whether it is listening to your favorite playlist, meditating, drawing, mindful movement, or (my personal favorite) putting together a puzzle, make sure to take a break just for you.

- Check In On Someone Else. No matter how things may look on the outside, there is usually more going on behind the mask. Physical distancing to slow the spread of COVID-19 is evidence-based and necessary; however, disconnecting from social networks can have devastating and long-term negative effects. As my pastor reminded me just a few days ago in his sermon from Genesis 2:18, the first problem in the Bible that God solved was that of solitude. Be sure that those around you know that they are not alone. Call, send a text, email, or send a card to let your friend, family, colleague, employee, or [insert relationship here] know that you are thinking of them and ask them the following questions:

- How are you doing?

- No, how are you really doing?

- Did you just lie to me?

And if they open up and share what is really going on behind the mask, take a page from the playbook of frontline peer supporters and be present and listen.

Editor's Note: Special Section on the Impact of COVID-19 on the Research Process

Crystal Lumpkins, PhD; Editor, Outlook

Crystal Lumpkins, PhD

In this issue of Outlook, we have continued our series of themed issues that capture current events and how those events impact both the field of behavioral medicine and also our everyday lives. COVID-19 continues to rage on and has become, in many ways, the largest contributing factor to a ‘new normal’ and the war within our minds, bodies and souls. This new normal has forced a shift in thinking for some and unfortunately debilitated others. Whether ‘it’ has facilitated or hindered progress, it is important that we strive to adapt. It’s in this time that adaptation can be beneficial in how we live life and also conduct our science. As a community-based researcher, I thought of how the pandemic has slowed research and was a bit frustrated but remembered that the work that many of us do is ‘applied’ and presents significant opportunities to make a positive difference. The articles in this issue capture these types of opportunities and shows us how, in a time of uncertainty, we can use our creativity, innovative thinking and also humanity to make an incredible difference in behavioral medicine.

In this issue, some of what you’ll read highlights the impact of COVID-19 on cardiovascular (CVD) research, physical activity, and running an Optimization trial during the pandemic. You will also hear from the voices of Black behavioral scientists who detail the impact on their research, careers and determination to forge on. Finally, our President, Dr. Monica Baskin, reminds us to take pause, make a true inventory of ourselves and to seek self-care. I encourage you to do just that – take time out for yourself as we all deserve to be healthy, happy and whole.

Collective Action in the Midst of COVID-19: How the SBM Health Policy Committee, SIGs and members are Going All IN

Akilah Dulin, PhD✉; Health Policy Committee Chair

Now more than ever, it is evident that SBM SIGs and members rise to overcome challenges in the midst of adversities. And, it is clear that we remain committed to translating evidence into action and advocating for policies that protect the most vulnerable communities.

Early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, the Health Policy Committee decided to revise our policy position statement process. We needed to become more nimble so we could disseminate timely, relevant and impactful statements on COVID-19 and health. Not only did we need to streamline and revise our process, but we also needed to rely upon the extensive expertise of SBM membership to help get the work done.

Based on these needs, we created a COVID-19 strategic initiative to: (1) omit the proposal step from the policy position statement process; (2) speed up the statement review times; and (3) reach out directly to SBM SIGs to coalesce around a specific, time-sensitive COVID-19 topic. The positive and enthusiastic response from SBM SIGs was overwhelming!

To pilot our strategic initiative, we reached out to the Health Equity SIG leadership to ask if they would lead a statement on health disparities. From this initial partnership, the SBM Policy Position Statements on COVID-19 and Health Equity and COVID-19 and Rural Health came to fruition. While in the midst of responding to the challenges of COVID-19, our communities were also left to process the senseless deaths of Black Americans. At a time when many feel frustrated and unsure of how to help address the enduring legacy of American racism, our Health Equity SIG and Health Policy Committee mobilized once again and developed a SBM Policy Position Statement on Policing Reform and Anti-Racist Research.

Based on the successes of our pilot, we reached out to the Child and Family Health and Violence and Trauma SIGs. The Child and Family Health SIG is working to finish a policy position statement on COVID-19 and mental health services while the Violence and Trauma SIG is finishing a statement on COVID-19 and intimate partner violence. Please be on the lookout for the release of these position statements on Twitter via @SBMHealthPolicy and be sure to disseminate them widely to your social networks.

In addition to our committee’s strategic COVID-19 initiative, individual SBM members continue to support the policy mission of SBM. Many of our fellow members’ delayed the release of their position statements due to the COVID-19 pandemic: Stigmatizing Language and Substance Use, SNAP and Small Food Stores, Public Charge Rule and Food Security, and the Promotion of Vaccination Adherence.

Other SBM members created new position statements on COVID-19; one statement aligned with SBM’s climate change initiative (COVID-19 and Heat Deaths) and another highlighted the critical issue of COVID-19 and food insecurity (Increasing Federal Food Assistance During COVID-19).

The scope and depth of policy work done by SBM SIGs and members in the past five months is astounding. We appreciate the positive response of SBM members and thank them for their efforts to mobilize and respond with policy initiatives specific to the current state of the world. For those of you interested in policy work, please consider submitting a SBM policy position statement.

The policy work also hinges on the efforts of the Health Policy Committee members. We would not be able to move this work forward without their insights. Therefore, I would like to recognize and extend a special thank you to Health Policy Committee members Brooke Bell; Amanda Blok, PhD, MSN, PHCNS-BC; Joanna Buscemi, PhD; Marian Fitzgibbon, PhD; Laura Hayman, MSN, PhD, FAAN, FAHA; Dawn Wilson King, PhD; Sarah Miller, PsyD; Lisa Quintiliani, PhD; and Reginald Tucker-Seeley, ScD.

Black Behavioral Scientists Forging On during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Sharon Cobb, PhD, MSN, MPH, RN, PHN; Shaila M. Strayhorn, PhD, MPH; Rhoda K. Moise, PhD; Christyl T. Dawson, PhD, MPH; Kamilah B. Thomas-Purcell, PhD, MPH, MCHES; Kimlin Tam Ashing, PhD✉; Health Equity SIG

In this brief, we share the voices of Black Behavioral Scientists -- from various regions, disciplines and stages of their career – and the impact COVID-19 has had on their professional lives.

COVID-19 has detrimentally affected our personal lives and our communities. At this same time, we are also intensely coping with racism and discrimination that is now at the forefront of societal self-examination and corrective action. COVID-19 is impacting our work, including research activities and community engagement. As our research addresses health disparities, our study populations are underserved, under-resourced and are the same communities who are disproportionately impacted and dying due to health inequities including COVID-19.

Impact of COVID-19 on our studies and career

Traditional research benchmarks, such as study implementation, IRB approvals, data collection (e.g., survey and biospecimen) and data analyses, are hindered given COVID-19 restrictions. Early career researchers, specifically postdoctoral fellows, are also faced with multiple challenges from individual to institution. Facing increased stress, these scientists must navigate new territory in virtual and remote environments. Mentoring is crucial and needed -- more so now than ever before due to the pandemic. Mentors and mentees are both adjusting to technology communications. Technology platform communications provide challenges for conducting research as well as training and mentoring, especially in the context of a new fellow. Mentors, with even more patience and flexibility, must be available to help new post-doctoral fellows to align expectations, develop obtainable goals, maintain work-life balance and expand their network.

Impact of COVID-19 on community responsive work

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in added responsibilities for behavioral scientists who conduct community engaged research with underserved minority communities. In the COVID-19 pandemic, these communities now have added health burdens including access to COVID-19 testing and vaccine readiness. As Black Behavioral Scientists, we are responding to these new and urgent community needs while still trying to conduct our research. Much of our data collection has shifted to communication technology platforms. Yet, technology-driven research with underserved study populations has its drawbacks including low technological literacy and capacity.

Forging On

We propose the following strategies that can assist researchers in helping communities affected by COVID-19 and that may also provide scientific bidirectional benefit:

- Institutions and scientists need to provide, facilitate and improve community access and utilization of technology communication methods (i.e. internet-based data collection, tele/video conferencing) for health intervention and research activities.

- Recommended Resources: a) Teleconferencing Platforms (i.e Zoom, Skype, WebEx, Google Calls), b) Podcasts (i.e. Spotify, Apple), c) Livestreams (i.e. Facebook, Instagram), d) Blogs (i.e. BioMed Central – Amplifying Black Voices).

- In partnership with community health leaders, institutions and scientists must heed the call to action and respond to the growing health disparities and health inequities by publicly contributing to corrective action for community health improvements.

- Recommended Resources: a) American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Cancer Disparities Progress Report, b) National Cancer Institute - Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences, c) NIH - Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research.

- Lastly, Behavioral Scientists should collaborate with other disciplinary fields on funding opportunities and resources for both COVID-19 and other chronic health issues to better address the biological and social determinants of health disparities. In partnership with diverse behavioral professionals, including nurses and social workers, community-directed efforts must increase promotion and uptake of COVID-19 protective behaviors, testing and vaccine preparedness among minority populations.

- Recommended Resources: a) Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities, b) National Cancer Institute - Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (NCI-CRCHD), c) Black Psychiatrists of America, d) National Association of Black Social Workers, d) Special Interest Groups - Society of Behavioral Medicine, e) AACR – Minorities in Cancer Research (MICR), f) National Health IT Collaborative for the Underserved.

As Black Behavioral Scientists, we must stay resilient in our efforts to improve health outcomes among underserved, vulnerable, and minority populations by developing innovative and collaborative strategies. We must be supportive and unified in order for all of us to thrive personally and professionally as we rise like the phoenix from the ashes of inequity.

Cardiovascular Behavioral Medicine: Research Reflections During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Alyssa Vela, PhD✉ and Allison Gaffey, PhD✉; Cardiovascular Disease SIG

Since early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic changed work, lifestyle, and quality of life in numerous ways. The impact of the virus on work-flow changes in medical and academic settings has been extensive. Cardiovascular behavioral health research may be more important than ever, as early signs indicate that the virus can majorly impact cardiac health, with unknown long-term physical and psychological consequences (Madjid, Safavi-Naeini, P., & Solomon, S.D., 2020). Given the rapid shift in research practice, implementation, and scope, the Cardiovascular Disease Special Interest Group-in-Formation (CVD SIG) reached out to members concerning how the pandemic has affected their CVD-oriented research.

Feedback from SIG members indicated that both benefits and challenges have resulted from COVID-19-related changes. Dr. Brie Turner-McGrievy, Associate Professor and Deputy Director of the TecHealth Center at the University of South Carolina, shared her experience conducting a study examining the impact diet has on CVD risk factors. The study originally included group-based classes with in-kitchen cooking demonstrations. Since switching to virtual meetings, group attendance has increased compared to in-person classes, but the research team has had difficulty completing the planned physiological assessments (i.e. weight, blood pressure, blood draws, and DXA scans). Other members described similar challenges that slowed, stopped, or prevented their research from starting all together.

Dr. Kimberly Garza, Associate Professor and Graduate Program Officer at the Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, planned to submit a proposal to collaborate with a local community-based cardiac rehabilitation facility. Her plans were tabled due to a surge of COVID-19 cases that temporarily closed the facility. Given the particularly severe impact on cardiac rehabilitation programs, Dr. Garza expects that this research will remain on hold. Dr. Garza’s experience speaks to the uncertainty many researchers are experiencing related to the nature and timing of projects, particularly studies including individuals with cardiovascular conditions that make them especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

As universities, hospitals, and research laboratories have re-opened and resumed their work, it has not been business as usual. Members of the CVD SIG reflected on the procedural, personnel, and spatial adjustments that are necessary to accommodate COVID-related restrictions, while also accounting for individual and public-health. Changes include increasing safety precautions for participants (and researchers) and adjusting timelines to accommodate a range of data collection details. Such changes are likely to mean research timelines will be longer and programs will be slower to re-activate. Further, for those who conduct human subjects research, they must also respond to changes in participant lifestyle, health behaviors, and mood that may impact participation and research outcomes. For example, Dr. Turner-McGrievy reported her participants have noted weight gain over the past several months that was attributed to COVID-19-related stress and changes in diet and physical activity levels while sheltering-in-place.

Heightened stress over the past several months has also impacted research participants’ comfort in attending research study visits. Dr. Kenneth Freeland, Professor of Psychiatry and Psychology at Washington University School of Medicine, shared his team’s experience conducting a randomized controlled trial among patients with comorbid heart failure and depression. After transitioning to phone-based study visits for the past several months, Dr. Freeland and his team surveyed participants to assess how they were coping with the pandemic and gauge their interest in returning to in-person visits. He reported that the study’s participants have demonstrated good insight into their risk and unique vulnerabilities, and thus, few are comfortable with resuming in-clinic visits. Overall, CVD SIG members indicated study participants are being appropriately cautious, and to quote Dr. Freeland “resilient.”

Cardiovascular behavioral medicine research has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in numerous ways. While it appears that not only the participants, but the researchers have been resilient over the past several months, it may be years before we can truly reflect on the impact of COVID-19 on CVD research implementation and outcomes.

Thank you to the members of the CVD SIG who contributed their insight and experiences to allow for the development of this article.

References

Madjid, M., Safavi-Naeini, P., & Solomon, S.D. (2020). Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: A review. JAMA Cardiology, 5(7),831-40. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286

The Impact of COVID-19 on School Nutrition Research: Barriers and Opportunities for Science-Informed Policy

Elizabeth Adams, PhD✉; Melanie Bean, PhD✉; Joanna Buscemi, PhD✉; Child and Family Health SIG

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP) provide essential nutrition to >30 million children daily. School closures due to COVID-19 have severely disrupted these programs, raising concerns for food insecurity, poorer nutritional intake, and widening health inequities.1,2 COVID-19 has also halted ongoing school nutrition research, creating barriers for empirical data to inform school food policy.

Rigorous scientific evidence is critically needed to inform policy decisions related to child nutrition programs. The current administration has already rolled-back some of the healthier NSLP and SBP guidelines mandated under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA),3 citing school nutrition programs’ inability to adhere to these (healthier) standards and increased plate waste, among others, lowering the nutrition standard for millions of children. However, these claims are anecdotal and inconsistent with available data.4 Several ongoing investigations were well-poised to provide additional rigorous scientific data to policymakers to help them make evidence-based decisions related to school nutrition programs. For example, via a large scale randomized controlled trial, Dr. Melanie Bean (PI), Child and Family Health Special Interest Group (SIG) Co-Chair and member of the Health Policy Council, is using digital imagery plate waste to evaluate the impact of salad bars on students’ fruit, vegetable, and energy intake (R01HD098732). Dr. Joanna Buscemi, Child and Family SIG member and Chair of the Health Policy Council was leading a mixed-methods study in Chicago Public Schools to assess high school student and caregiver predictors of participation in the NSLP across 5 schools serving systemically oppressed populations. Active data collection is paused for both studies due to school closures with no real timeline for when the projects will be able to resume.

If we, and others, are unable to fully execute these school-based investigations, then scientific evidence available to policymakers will be limited. The Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act, which included the HHFKA, has not been reauthorized since 2010. Discussions were underway to pass the Reauthorization Act when COVID-19 occurred, but Congress refocused its efforts to pandemic relief. While the NSLP and SBP continue to operate through annual appropriations, the Reauthorization Act provides an opportunity to improve and strengthen these programs based on the latest scientific evidence. Consequently, in the absence of new evidence, other factors (e.g., cost) and entities (e.g., lobbyists, food industries) might carry a greater weight in driving forthcoming policy changes to the NSLP and SBP.

Despite barriers to conducting nutrition research in schools, the pandemic may require that Society of Behavioral Medicine (SBM) members quickly pivot to evaluate COVID-19 related changes to the NSLP (e.g., waivers and meal distribution methods) and examine their impact on children’s dietary intake and food security. Indeed, child nutrition is an SBM policy priority area for the next 3 years, highlighting the need for members to continue to champion these issues in our current context in both their research and advocacy efforts. With >30 million children relying on school meals, high nutrition standards are of paramount importance to optimize the dietary intake of the most vulnerable youth.

References

- Fleischhacker S, Campbell E. Ensuring equitable access to school meals. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(5):893-897.

- Dunn CG, Kenney E, Fleischhacker SE, Bleich SN. Feeding low-income children during the COVID-19 pandemic. New Eng J Med. 2020;382:e40.

- Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. One Hundred Eleventh Congress of the United States of America, 2nd Session. S. 2010:3307.

- Buscemi J, Odoms-Young A, Yaroch AL, et al. Retain school meal standards and healthy school lunches. Society of Behavioral Medicine Position Statement. January 2018. https://www.sbm.org/UserFiles/file/SBMpolicybrief_SchoolLunchStandards.pdf

Physical Activity Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethos of a Problem.

Yves Paul Mbous, MEng✉ and Rowida Mohamed, MSc✉; Health Decision Making SIG

The heightened emphasis on physical activity (PA) promotion stems from the vast array of advantages it confers but also from the burden of physical inactivity. Recent evidence among PA benefits include: improved bone health, better cardiovascular health, increased cognitive functioning, decreased cancer, diabetes, anxiety and depression risks, reduced risk of mortality, and better quality of life.1 Weekly minimums of 150 minutes of moderate PA or 75 minutes of vigorous PA are necessary to achieve these benefits. Conversely, in the United States, physical inactivity increases mortality and additionally warrants healthcare spending worth at least $117 billion.2, 3 Herein lies the utility of evidence-based interventions. For when products of research are used effectively in communities, they can bring forth changes in intention and behavior necessary to engage and adhere to regular exercise.4 However, research endeavors in this field have been radically upended since the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The enforcement of social distancing measures has inadvertently favored auspicious conditions for sedentary behavior and physical inactivity. Ironically, the growing incidence of mental health conditions5 during this phase has warranted renewed calls for research to provide appropriate evidence guidelines for effective community-based PA interventions.6

Researchers are faced with many problems that hamper the conduct of objective work. The nature of these issues is mostly tied to participants’ recruitment, study design, logistics, and general attitudes. Typically, recruitment takes place at public avenues such as hospitals, primary care clinics, workplaces, churches, barbershops, health clubs and via door-to-door visits. Since the shutdown, most of these avenues have been intermittently closed as a result of enforcement measures and reluctance of people to engage with the outside world where they could be at risk of infection. Although coming in contact with potential participants is still possible via the Internet or mail, initiating contact via the former is not always guaranteed in rural areas or other regions of restricted access. Study design is impeded through the mechanisms of the intervention. Researchers must now frame exercise types, plans and regimens adapted to indoor spaces but that also meet the recommended duration and intensity. Parallelly, there is also a shortage of adequate measurement tools. Accelerometers and pedometers, already limited in the information they can provide (accuracy and reliability)7, 8, use sensors that best record ambulatory exercise. In limited spaces, objective measurement of “sedentary” PA is not always feasible; the same can be said about compliance and adherence patterns. Subjective measures carry an even greater unreliability as they rely on the appreciation of the participants and their proclaimed compliance to the program. Further, it is also easy to notice how logistics (indoor space, Internet access, equipment) would render home-based interventions less appealing for communities of low economic status. Avoidance of social interactions as well as different priorities (job search amidst increasing furlough) could lessen the incentive to partake in PA research intervention especially for high-risk groups and vulnerable populations with limited resources.

These are some of the issues that need to be addressed to strengthen PA research. Recent works are making use of cell phone applications (GoToMeeting platform) to guide interventions.9 However, the objective remains to conceptualize research that would subsequently lead to adequate behavior uptake during this pandemic. Vulnerable populations seem more at risk: an invitation for policymakers to act where they are most needed. To ensure equitable access to physical activity opportunities, the American College of Sports Medicine, among other researchers, has proposed to improve access to public parks and green spaces and to create built environments in close proximity to all but primarily vulnerable populations.10, 11 This call for action is directed to policymakers, stakeholders, and researchers to actively evaluate and implement policies pertaining to these recommendations.

References

- Piercy, K. L., Troiano, R. P., Ballard, R. M., Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Galuska, D. A., … Olson, R. D. (2018). The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14854

- Carlson, S. A., Adams, E. K., Yang, Z., & Fulton, J. E. (2018). Percentage of Deaths Associated With Inadequate Physical Activity in the United States. Preventing chronic disease. doi:10.5888/pcd18.170354

- Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Pratt, M., Yang, Z., & Adams, E. K. (2015). Inadequate Physical Activity and Health Care Expenditures in the United States. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2014.08.002

- Brownson, R. C., Ballew, P., Dieffenderfer, B., Haire-Joshu, D., Heath, G. W., Kreuter, M. W., & Myers, B. A. (2007). Evidence-Based Interventions to Promote Physical Activity. What Contributes to Dissemination by State Health Departments. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.011

- Rajkumar, R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

- Sallis, J. F., Adlakha, D., Oyeyemi, A., & Salvo, D. (2020). An international physical activity and public health research agenda to inform coronavirus disease-2019 policies and practices. Journal of Sport and Health Science. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.005

- Goode, A. P., Hall, K. S., Batch, B. C., Huffman, K. M., Hastings, S. N., Allen, K. D., … Gierisch, J. M. (2017). The Impact of Interventions that Integrate Accelerometers on Physical Activity and Weight Loss: A Systematic Review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. doi:10.1007/s12160-016-9829-1

- Aparicio-Ugarriza, R., Mielgo-Ayuso, J., Benito, P. J., Pedrero-Chamizo, R., Ara, I., & González-Gross, M. (2015). Physical activity assessment in the general population; instrumental methods and new technologies. Nutricion hospitalaria. doi:10.3305/nh.2015.31.sup3.8769

- Thombs, B. D., Kwakkenbos, L., Carrier, M. E., Bourgeault, A., Tao, L., Harb, S., … Varga, J. (2020). Protocol for a partially nested randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the scleroderma patient-centered intervention network COVID-19 home-isolation activities together (SPIN-CHAT) program to reduce anxiety among at-risk scleroderma patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110132

- Rebecca Hasson PD. F, Jim Sallis PD. F, Nailah Coleman MD. F, Navin Kaushal PD., Vincenzo Nocera MS., NiCole Keith PD. F. The missing mandate: Promoting physical activity to reduce disparities during COVID-19 and beyond. American College of Sports Medicine Blog. https://www.acsm.org/blog-detail/acsm-blog/2020/06/03/promoting-physical-activity-reduce-disparities-during-covid-19. Published June 30, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2020.

- Slater SJ, Christiana RW, Gustat J. Recommendations for keeping parks and green space accessible for mental and physical health during COVID-19 and other pandemics. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17(17). doi:10.5888/PCD17.200204

Yoga Practice in the Time of COVID-19: Perspectives from Two Expert Researchers

Lucy Finkelstein-Fox, MS✉; Integrative Health and Spirituality SIG

The COVID-19 pandemic has made an immeasurable impact on the daily lives of clinicians, researchers, and the populations they serve. Over the past several months, members of the (newly merged) Integrative Health and Spirituality SIG have found creative ways to leverage technology as a means to safely deliver yoga and other mind-body interventions to a range of populations.

Yoga is a mind-body practice incorporating aspects of meditative movement, breathing, and spirituality. Based on the recent experiences shared by experts Crystal Park, PhD, Professor of Psychology at the University of Connecticut, and Lisa Uebelacker, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Assistant Director of Psychosocial Research at Butler Hospital, we provide several considerations for the practice of yoga during the COVID-19 pandemic below.

- Minimize Risk. Depending on the characteristics of participants, different methodological adaptations may be necessary to minimize the risk of yoga. For example, Dr. Uebelacker notes that it is important for participants at elevated risk for COVID-19, including those of older age, to stay home and receive clinical services via video. For participants with physical limitations that might necessitate live instructor modifications to prevent injury (e.g., low back pain), Dr. Park describes that she and her team have considered adapting interventions to be delivered in large, socially-distanced spaces (e.g., an open gymnasium) and plan to be flexible as public health recommendations evolve over the coming months.

- Promote Social Connection. Video platforms such as Zoom and WebEx are now commonly used by healthcare practices as well as commercial yoga and fitness studios, making them familiar to many participants in yoga interventions. However, web-based delivery may make it difficult for intervention participants to establish informal social relationships, which Dr. Park notes are “a big part of people’s experience in any intervention.” To enhance perceptions of social connection in an online yoga study, Dr. Uebelacker and her team have scheduled time for intervention participants to virtually meet one-to-one with their yoga instructor at the start of the program.

- Create a Peaceful Environment. Dr. Park and her collaborators have been working hard to make remote yoga “feel like something special.” Whereas studios are typically decorated with special textiles, meditation cushions, or spiritual images that orient practitioners to the sacred space, many people are now practicing yoga in spaces they also use for work or other activities (e.g., bedroom). To enhance separation between space used for yoga and other activities, practitioners may consider making small changes to their environment like lighting candles or playing music.

Despite the new challenges presented by COVID-19, these changes may also pave the way for positive developments in yoga practice, reducing many traditional barriers to access (e.g., transportation, cost, scheduling). Dr. Park anticipates that the shift to remote yoga practice may help participants to cultivate the “inward focus” emphasized in yoga philosophy. In one of Dr. Uebelacker’s recent interventions, the researchers similarly speculated that teenaged participants might feel less self-conscious when practicing at home.

Yoga, meditation, and other integrative and spiritual practices may be useful resources for tolerating the uncertainty of COVID-19. Dr. Uebelacker describes the benefit of focusing on the here and now: "Practicing being in-person, in the moment, is a good reminder that we only need to get through this moment, and shifts attention away from questions like ‘how long is this going to last?” She also notes that another benefit of yoga practice comes from physical poses, or asanas, which may counteract the deleterious effects of sedentary behavior that has increased as individuals work from home.

Finally, Dr. Uebelacker also encourages those interested in remote yoga practice to look into yoga opportunities nearby. “Check out your local yoga studio to see what they are offering virtually. It can be nice to do ‘live’ yoga – even if you are in your own home. If you do live virtual classes, be sure to pay for them.”

SBM members interested in online yoga may also consider the following resources:

Interested in joining the Integrative Health and Spirituality SIG? Visit the SIG webpage to learn more and add the IHS SIG to your SBM member profile to stay up to date.

Let’s discuss your thoughts about this article on Twitter with our new hashtag #IntegrativeSBM!

Running an Optimization Trial during COVID-19: Adaptations and Considerations from the Field

Kate Guastaferro, PhD, MPH✉ and Rachel D. Wells, PhD✉; Optimization of Behavioral and Biobehavioral Interventions (OBBI) SIG Chairs

On top of heightened personal and professional stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists have needed to quickly adapt intervention studies for remote delivery and/or assessment, modify study objectives with funders, and even alter outcomes or endpoints. The complexity of adaptations and difficult decisions is largely contingent upon the experimental design in use. Here, we interviewed two SBM member-led research teams to learn how they adapted their active optimization trials during COVID-19.

Briefly, an optimization trial, a feature of the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST),1 is an experiment designed to identify which components produce the best expected outcome while balancing constraints (e.g., time, cost). Often, the optimization trial uses a factorial experimental design wherein two or more factors (i.e., candidate intervention components) with two or more levels are manipulated with the purpose of identifying the individual effect of each factor on average on the desired outcome (main effect) as well as whether the effect of a factor varies depending on the level of other factors (interaction).

Drs. Sarabeth Broder-Fingert & Emily Feinberg (Boston University)

What is the purpose of your study?

Our study seeks to examine implementation strategies for Family Navigation, an evidence-based care management strategy. Using a 24 full factorial experiment we aim to recruit 304 families to determine what combination of four components (and at what level) have the greatest effect on completion of family behavioral health goals.2

What adaptations have you made and what have you had to consider in light of needed adaptations?

We have not had to directly alter the design of the optimization trial, but instead had to consider the factor designed to compare in-clinic versus community family navigation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, neither component could be delivered as designed – families are not coming into the clinic and Navigators cannot do home visits. Instead, families are receiving the “COVID version” wherein personal virtual visits are done via video or audio call.

We are considering three options. First, we could keep doing as we are and at some point, return to services as planned. Second, keep randomizing to all 16 experimental conditions, but in analyses collapse the factor (effectively not treating it as an experimental factor). These options allow us to deal with this unplanned scenario analytically. However, a third option might be to examine the core elements of the component and see if there are functional differences between the elements of the intervention delivered by the clinic or community health worker.

Dr. J. Nick Dionne-Odom (University of Alabama at Birmingham)

What is the purpose of your study?

The purpose of our study is to pilot test an optimization trial approach to develop and refine the decision partnering skills of family caregivers of persons with newly-diagnosed advanced cancer using a 23 factorial design with 40 family caregivers of persons with newly-diagnosed advanced cancer.

What adaptations have you made and what have you had to consider in light of needed adaptations?

We haven't had to adapt the design in significant ways from what we originally planned. Our intervention has always been delivered primarily telephonically and so our general operations were able to perform robustly even after COVID-19. We did have to convert our in-person recruitment approach to one that was done wholly by mail and phone.

We had to consider how to build interest in our study and trust with our interventionists without the aid of in-person contact.

We asked our optimization trialists to offer some advice, rooted in their experience and success in adapting their optimization trial to the COVID-19 pandemic:

Drs. Broder-Fingert & Feinberg: “We think two things prepared us well to adapt to the uncertain times of COVID-19. First, we had a really good, experienced project manager who was able to help execute, and trouble-shoot, a rigorous experimental design. Second, our familiarity with the component allowed us to consider how each component was implemented in each level of the factor and identify salvageable research questions. All in all, we are actually on track with our recruitment goals. Now that people are returning to the clinic, we are getting more referrals for mental and behavioral health needs.”

Dr. Dionne-Odom: “Organization and written detailed protocols for study processes are key to smooth operations. We have separate interventionists scripts, toolkit materials, and charting templates, and a robust fidelity monitoring plan of all recorded intervention sessions to ensure participants receive their assigned condition.”

References

- Collins LM. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). New York: Springer; 2018.

- Broder-Fingert S, Kuhn J, Sheldrick RC, et al. Using the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) framework to test intervention delivery strategies: A study protocol. Trials. 2019;20(1):1-15. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3853-y

Research with Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19: Strategies, Ethical and Safety Considerations

Bushra Sabri, PhD✉; Violence and Trauma SIG Co-Chair

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a significant global public health concern, with the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating conditions for women in abusive relationships. Therefore, there is need for research and interventions focusing on preventing IPV and supporting IPV survivors during the pandemic. Remote communication for research has been implemented as the primary alternative to in-person interactions during the pandemic but have nonetheless been challenging. The challenges pertain to conducting safe and accurate data collection, guaranteeing privacy and confidentiality under quarantine conditions, providing care or referrals when there is limited availability and access to services for participants in immediate danger and overcoming safety, ethical and methodological challenges with recruitment or remote data collection.1, 2 Research3 shows that some of the best digital media through which to safely recruit IPV survivors remotely include Facebook groups, sponsored twitter posts for IPV survivors, zoom, IPV-related forums, Instagram, and radio/TV news. Other reported strategies are posting flyers in grocery stores, and recruiting through community-based organizations, places of worship and word of mouth.3

This article describes safety, ethical and methodological challenges that researchers may encounter in collecting data from IPV survivors during the pandemic and recommend strategies for remote data collection from survivors.

Safety, Ethical and Methodological Challenges in Communicating with Survivors for Research during the Pandemic:

- Abusive partners being home where calling or texting is more heavily monitored, and in some cases, denied by the partner3

- Difficulty in having a minimum 20-30-minute conversations, which is necessary to understand a survivor’s situation for research purposes3

- Some survivors not being comfortable with virtual platforms or using phone services, either because of partner surveillance or because of the preference for personalized, face to face interaction3

- Lack of access to technology or not having access to the internet, which makes digital communication difficult or unreliable3

- Even if digital communications are possible, abusive partners hacking into emails and phones3

- Children being at home because of school-at-home and quarantine orders, so children may be present when a researcher or provider is in contact with survivors which can arouse fear and anxiety in the children if they overhear anything3

- Too frequent phone calls or text messages can arouse suspicion in partner3

Recommendations for Remote Data Collection with Survivors

- Scheduling a contact time when participants are alone to ensure privacy and confidentiality and providing quick exit options3

- Using code words (e.g., calling from a health insurance company) for phone calls or text in case the abusive partner picks up instead of the intended participant. These code words can be developed with participants early in the research process and personalized for each participant. 3

- For email contact, ensuring that survivors use their own email accounts and change password frequently to prevent abuser from knowing about their participation in an IPV-related study. 3

- Developing referral mechanisms as well as adverse event protocols to ensure rapid response for survivors or data collectors in danger of immediate harm.1, 2

- Having strategies in place to minimize distress for participants as well as the researchers such as virtual debriefs and built-in breaks.1

- Training data collectors in trauma-informed data collection techniques and safety, and ethical considerations when working with survivors. The key is to always ensure the safety of survivors.

Research with survivors of IPV calls for ethical and safety protocols for remote data collection especially during the pandemic because of multiple risks and vulnerabilities of survivors. This includes adapting methods when needed to ensure survivors’ safety and well-being.

References

- Guedes, A. Challenges in collecting violence data: Ethical, methodological and research priorities during COVID, based on conversation with experts. Presentation by The Nursing Network on Violence Against Women International

- Peterman, A., Bhatia, A., & Guedes, A. (2020). Remote data collection on violence against women during COVID-19: A conversation with experts on ethics, measurement & research priorities (Part 1). Accessed from https://reliefweb.int/report/world/remote-data-collection-violence-against-women-during-covid-19-conversation-experts

- Sabri, B. (2019-2024). An Adaptive Intervention to Improve Health, Safety and Empowerment Outcomes among Immigrant Women with Intimate Partner Violence Experience (R01MD013863), 08/05/2019-02/29/2024, Sabri (PI). Funded by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Vicarious Trauma Among Healthcare Workers

Em V. Adams, PhD, CTRS✉; Violence and Trauma SIG

In pre-COVID-19 times an estimated 16% of emergency room physicians and 20-30%1 of nurses met the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).2 Notably, rates of suicide among physicians was 40 times higher than the general population for male physicians and 130 times higher for female physicians.3

While we do not have data to report the impact of the global pandemic on these numbers, we can identify factors that may lead to increased risk of trauma, burnout, and suicide. These factors include witnessing numerous patient deaths, working with grieving families, being isolated, lack of personal protective equipment, and anxiety over personal health and the health of loved ones.4

For some, the risk of PTSD is heightened after the initial stressor has resolved. Physician, Wendy Dean wrote “My medical training taught me how to get through a crisis…My training did not teach me what the other side of those crises would look like, though, when the action of crisis was replaced by the stillness of recovery. There was no plan or contingency for when, in an unguarded moment, the door to my emotions blew open and the pent-up tsunami of grief and fear and sadness and anger and insecurity and doubt swept over me.”4 As parts of the country move into recovery, healthcare agencies need specific plans in place to ensure the safety and emotional well-being of healthcare workers. Outlined below are some suggestions for adding to a strategic plan to recover from trauma.

Create a culture of peer support. Teams should have an opportunity to debrief after a difficult crisis, and supervisors might consider implementing a buddy system so each person has someone checking on them.5 Clinical supervision should include opportunities to discuss personal feelings regarding difficult events. Additionally, managers can intentionally create other opportunities for peer support to occur.

Provide resources for workers to get psychological counseling. If your agency does not already have an affiliation agreement with a counseling center, help can be found on the following sites: Trauma Recovery Network https://www.emdrhap.org/content/trn/what-do-trn-associations-do/; Frontline Workers Counseling Program https://www.fwcp.org/

Make a strategic plan for rest and recovery. After natural disasters or deployment, there is typically a planned rest period before people are expected to move on to the next task. While there is not a clear end to COVID-19, there should be a strategic plan in place for ensuring employees get rest, vacation days, mental health days, and time to recover and seek treatment as desired should be a priority.5

Communicate resources outside of counseling. Pospos et al. conducted a literature review on available apps for preventing burnout and suicide for medical workers.6 The following apps were recommended based on the literature: Breath2Relax (breathwork) Headspace, guided meditation audios (mindfulness), MoodGYM, Stress Gym (web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), and Stay Alive, Virtual Hope Box (suicide prevention apps). For some, apps may be a more accessible option for improved coping strategies in distressing moments.

In summary, those of us working in behavioral health may or may not be working at the forefront of the COVID-19 response. However, most of us have been impacted or have colleagues who have been impacted in profound ways. It’s up to all of us to create a culture that prioritizes well-being of all employees.

References

- Schernhammer ES. Taking Their Own Lives – The High Rate of Physician Suicide. N Eng J Med. 2005;352(24):2473–2476.

- Hosseininejad, S. M., Jahanian, F., Elyasi, F., Mokhtari, H., Koulaei, M. E., & Pashaei, S. M. (2019). The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among emergency nurses: a cross sectional study in northern Iran. BioMedicine, 9(3).

- Kalmoe, M. C., Chapman, M. B., Gold, J. A., & Giedinghagen, A. M. (2019). Physician suicide: a call to action. Missouri medicine, 116(3), 211.

- Dean, W. (2020). Suicides of two health care workers hint at the Covid-19 mental health crisis to come. Stat News Retrieved from: https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/30/suicides-two-health-care-workers-hint-at-covid-19-mental-health-crisis-to-come/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2018) First Responders: Behavioral Health Concerns, Emergency Response, and Trauma. Supplemental Research Bulletin. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/dtac/supplementalresearchbulletin-firstresponders-may2018.pdf

- Pospos, S., Young, I. T., Downs, N., Iglewicz, A., Depp, C., Chen, J. Y.,& Zisook, S. (2018). Web-based tools and mobile applications to mitigate burnout, depression, and suicidality among healthcare students and professionals: a systematic review. Academic psychiatry, 42(1), 109-120.

We Need to Start Talking About the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine NOW

Monica L. Kasting, PhD✉ and Katharine J. Head, PhD✉; Health Decision Making SIG

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has dominated our lives for most of 2020. It is the lead story in the news and has affected nearly every aspect of daily life. While the current pandemic is unprecedented, controlling infectious disease through messaging is exactly what we as social and behavioral researchers have been studying for decades, making our research uniquely relevant for the times. Perhaps the greatest challenge is how to simultaneously communicate risk of infection, promote preventive behaviors, and discuss vaccine development. Even though a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is not yet available, we believe we should begin communicating with the public about a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine now, to ensure optimal uptake once it becomes available.

SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Intent

In May 2020, we conducted a survey of adults living in the U.S. and assessed, among other variables, their SARS-CoV-2 vaccine intentions.1 We found that intentions were high (M=5.23/7 point scale), and increased when we included a strong healthcare provider recommendation (M=5.47). However, these intentions varied significantly based on several important demographic and health belief variables. Modifiable health belief variables like perceived threat, worry, and altruism were positively associated with higher vaccination intent. Notably, less education and conservative ideology were significantly associated with lower vaccination intent. These differences suggest that some sub-groups may forego vaccination, and therefore leave some communities at higher risk. Social and behavioral scientists have the tools to address these differences through evidence-based communication strategies.

Vaccine Communication

Vaccination promotion is challenging even when there is not a global pandemic. Given there are already attacks on the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine from the anti-vaccine industry,2 along with the decision by the U.S. federal government to name the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development process “Operation Warp Speed,”3 social and behavioral scientists may already be behind in their need to address vaccine promotion. The findings from our survey – specifically, the association of vaccine intent with perceived threat, worry, and altruism – give us important starting points for campaign and intervention development. While this is certainly not an exhaustive list, several important health behavior concepts and models are useful to reference:

- Inoculation Theory posits that exposing people to potential counterarguments about the new vaccine will help them generate resistance to these negative messages that they may encounter in the future (e.g., the belief that the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was developed quickly and is therefore unsafe).4 It will be helpful in anticipation of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to begin implementing aspects of Inoculation Theory now, before people have encountered too much more misinformation. Furthermore, implementing aspects of Inoculation Theory now, and acknowledging the negative messages, may help avoid a “boomerang effect,” which describes the effect of only giving people positive messages, without acknowledging risks or limitations.5 By developing messages that expose people to potential counterarguments and acknowledge possible risks, we can effectively communicate that the benefits far outweigh the risks and improve vaccine uptake.

- Diffusion of Innovation posits that preventive innovations are particularly hard to promote.6 Consistent with diffusion of innovation work, we will need to rely on media for spreading accurate and timely information about the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, but it will be incumbent on opinion leaders within our interpersonal networks to promote vaccine uptake.7 As noted in our survey findings, healthcare providers will be a particularly important opinion leader in this context, but other important opinion leaders may include politicians, religious leaders, and business owners.

- Extended Parallel Process Model can enable us to capitalize on the natural perceived threat that many people feel right now, and pair it with an effective and safe “response” in the form of a vaccine that will hopefully be easy for people to obtain.8

Conclusion

There are close to 200 vaccines in various stages of production, and some have moved to Stage III clinical trials.9 A safe and effective vaccine that is widely available and acceptable to the public will be essential to ending the COVID-19 pandemic. As social and behavioral scientists, we have the tools to ensure high acceptance and uptake of this vaccine. Never has our research and expertise been more important. Let’s get to work.

References

- Head KJ, Kasting ML, Sturm L, Hartsock JA, Zimet GD. A national survey assessing SARS-CoV-2 vaccination intentions: Implications for future public health communication efforts. Under Review. 2020.

- Ball P. Anti-vaccine movement could undermine efforts to end coronavirus pandemic, researchers warn. Nature. 2020;581(7808):251.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Fact Sheet: Explaining Operation Warp Speed. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/06/16/fact-sheet-explaining-operation-warp-speed.html. Published 2020. Updated 16 June 2020. Accessed 20 August 2020.

- Compton J, Jackson B, Dimmock JA. Persuading Others to Avoid Persuasion: Inoculation Theory and Resistant Health Attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7(122).

- Kasting ML, Cox AD, Cox D, Fife KH, Katz BP, Zimet GD. The effects of HIV testing advocacy messages on test acceptance: a randomized clinical trial. BMC medicine. 2014;12:204.

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addictive behaviors. 2002;27(6):989-993.

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4th edition. Simon and Schuster; 2010.

- Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs. 1992;59(4):329-349.

- Corum J, Grady D, Wee S, Zimmer C. Coronavirus Vaccine Tracker. The New York Times. 2020. Accessed: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.html

Optimizing the New Normal: Pivoting an In-Person Trauma and Syndemic-responsive HIV Care Intervention to a Virtual Platform in the era of COVID-19

Jamila K. Stockman, PhD, MPH✉; Katherine M. Anderson, MPH; Sara Giovanna Carr, LMFT, MA; Marylene Cloitre, PhD; and Laramie R. Smith, PhD; HIV and Sexual Health SIG

Like HIV, the novel COVID-19 pandemic is disproportionately impacting people of color1 and invoking new HIV care challenges.2 In the US, women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA) are already less likely than men to adhere to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and be virally suppressed,3,4 with women of color particularly affected.4 Syndemic (e.g., co-occurrence of violence, trauma, substance use, and poor mental health)5,6 and socio-structural (e.g., medical mistrust, stigma, social isolation)7-14 barriers exacerbate poor HIV care outcomes.15,16 To address this gap, we implemented the BRIDGES program in 2019, an in-person peer navigation intervention for syndemic-affected WLHA.

The BRIDGES program harnesses evidence-based trauma-informed psychoeducation, and is designed to build skills to cope with syndemic-related affective distress and activate social support networks. The ultimate goal is to improve retention in HIV care and ART adherence among syndemic-affected WLHA. BRIDGES participants take part in weekly in-person one-on-one peer navigation sessions with a WLHA-peer navigator experienced with accessing HIV care, coupled with 6 weeks of 2-hour psychoeducation group sessions co-facilitated by a peer navigator and licensed clinical therapist. Group sessions addressed topics relevant to WLHA’s lives, spanning from emotional awareness/regulation to relationship building.

One month post-implementation, the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly fell upon us, requiring an adjustment to a new normal – and a pivot in our tactic to support WLHA. The university issued an immediate directive to halt all in-person research- a logical public health response. Yet, ending intervention activities with BRIDGES participants could have resulted in harm, particularly in the context of a pandemic: increased social isolation, depressive symptoms, substance use, and violence already exacerbated by COVID-1917,18 could be compounded by the removal of services and support BRIDGES provides. We found ourselves balancing risk of COVID-19 with the principle of beneficence, to “maximize possible benefits while minimizing possible harms.”19 Ultimately, it was our due diligence to transition BRIDGES from the in-person format to a web-based virtual platform. Within one week, peer navigation one-on-one sessions occurred through phone, text, or Zoom video, while psychoeducation support group sessions and survey assessments (baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-up) occurred through Zoom video. BRIDGES staff prepared participants by holding introductory Zoom video-based sessions one day prior to their first “BRIDGES virtual session”, allowing women to become familiar with the technology and technical issues to be resolved.

We found the pivot from in-person to a virtual-based format has been acceptable, feasible, and well-received by participants. Participants have shared that the virtual format is easy, convenient, fits into their routine, and allows for more social connections without additional effort or risk- even to the extent of preferring the virtual format over the in-person format. Virtual sessions mitigated the anxiety syndemic-affected WHLA experience when having to leave home or get ready to meet people, a barrier preventing them from participating in in-person intervention programs. Taken together, the virtual format circumvents social isolation, fosters social support, and addresses barriers to in-person peer navigation-social support approaches. The COVID-19 pandemic is challenging; but, this pivot to innovation may prove a new and better way to support syndemic-affected WLHA.

For more information about the BRIDGES program and our syndemic and trauma related HIV research please contact Jamila K. Stockman, PhD, at jstockman@health.ucsd.edu or visit our study websites at https://istriveresearchlab.com.

References

- Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, et al. Disparities In Outcomes Among COVID-19 Patients In A Large Health Care System In California. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2020:101377hlthaff202000598.

- Shiau S, Krause KD, Valera P, Swaminathan S, Halkitis PN. The Burden of COVID-19 in People Living with HIV: A Syndemic Perspective. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(8):2244-2249.

- Geter A, Sutton MY, Armon C, et al. Trends of racial and ethnic disparities in virologic suppression among women in the HIV Outpatient Study, USA, 2010-2015. PloS one. 2018;13(1):e0189973.

- Geter A, Sutton MY, Armon C, Buchacz K. Disparities in Viral Suppression and Medication Adherence among Women in the USA, 2011-2016. AIDS and behavior. 2019;23(11):3015-3023.

- Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS, part 2: Further conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology. 2006;34(1):39-54.

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Medical anthropology quarterly. 2003;17(4):423-441.

- Geter A, Sutton MY, Hubbard McCree D. Social and structural determinants of HIV treatment and care among black women living with HIV infection: a systematic review: 2005-2016. AIDS care. 2018;30(4):409-416.

- Lipira L, Williams EC, Huh D, et al. HIV-Related Stigma and Viral Suppression Among African-American Women: Exploring the Mediating Roles of Depression and ART Nonadherence. AIDS and behavior. 2019;23(8):2025-2036.

- Filiatreau LM, Wright M, Kimaru L, et al. Correlates of ART Use Among Newly Diagnosed HIV Positive Adolescent Girls and Young Women Enrolled in HPTN 068. AIDS and behavior. 2020.

- Nemoto T, Iwamoto M, Suico S, Stanislaus V, Piroth K. Sociocultural Contexts of Access to HIV Primary Care and Participant Experience with an Intervention Project: African American Transgender Women Living with HIV in Alameda County, California. AIDS and behavior. 2020.

- Takada S, Ettner SL, Harawa NT, Garland WH, Shoptaw SJ, Cunningham WE. Life Chaos is Associated with Reduced HIV Testing, Engagement in Care, and ART Adherence Among Cisgender Men and Transgender Women upon Entry into Jail. AIDS and behavior. 2020;24(2):491-505.

- Turan B, Rice WS, Crockett KB, et al. Longitudinal association between internalized HIV stigma and antiretroviral therapy adherence for women living with HIV: the mediating role of depression. AIDS (London, England). 2019;33(3):571-576.

- Gaston GB, Alleyne-Green B. The impact of African Americans' beliefs about HIV medical care on treatment adherence: a systematic review and recommendations for interventions. AIDS and behavior. 2013;17(1):31-40.

- Pellowski JA, Price DM, Allen AM, Eaton LA, Kalichman SC. The differences between medical trust and mistrust and their respective influences on medication beliefs and ART adherence among African-Americans living with HIV. Psychology & health. 2017;32(9):1127-1139.

- Blashill AJ, Bedoya CA, Mayer KH, et al. Psychosocial Syndemics are Additively Associated with Worse ART Adherence in HIV-Infected Individuals. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(6):981-986.

- Sullivan KA, Messer LC, Quinlivan EB. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS (SAVA) syndemic effects on viral suppression among HIV positive women of color. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2015;29 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S42-S48.

- Panchal N, Kamal R, Orgera K, et al. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. 2020; https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Bosman J. Domestic Violence Calls Mount as Restrictions Linger: ‘No One Can Leave’. The New York Times2020.

- Adashi EY, Walters LB, Menikoff JA. The Belmont Report at 40: Reckoning With Time. American Journal of Public Health. 2018;108(10):1345-1348.

Fostering Collaborations Between SBM and GSA: An Interview with Dr. Barbara Resnick

Kathi L. Heffner, PhD✉; Jaime Hughes, PhD, MPH, MSW✉; Elizabeth Orsega-Smith, PhD✉; Aging SIG

Barbara Resnick, PhD, CRNP, FAAN, FAANP

The United States population of adults aged 65 and older is expected to reach around 64 million in 10 years. Indeed, the number and proportion of older adults in virtually all segments of the population is increasing worldwide, a phenomenon known as population aging. With population aging comes compelling challenges for behavioral medicine, such as expanding the portfolio of evidence-based, effective behavioral medicine interventions to promote healthy aging, and ensuring health policies positively impact on the health, well-being, and care of older adults. Population aging also comes with incredible opportunities for behavioral medicine -- science and practice -- to benefit from the knowledge, wisdom, and experience of individuals who have lived long lives.

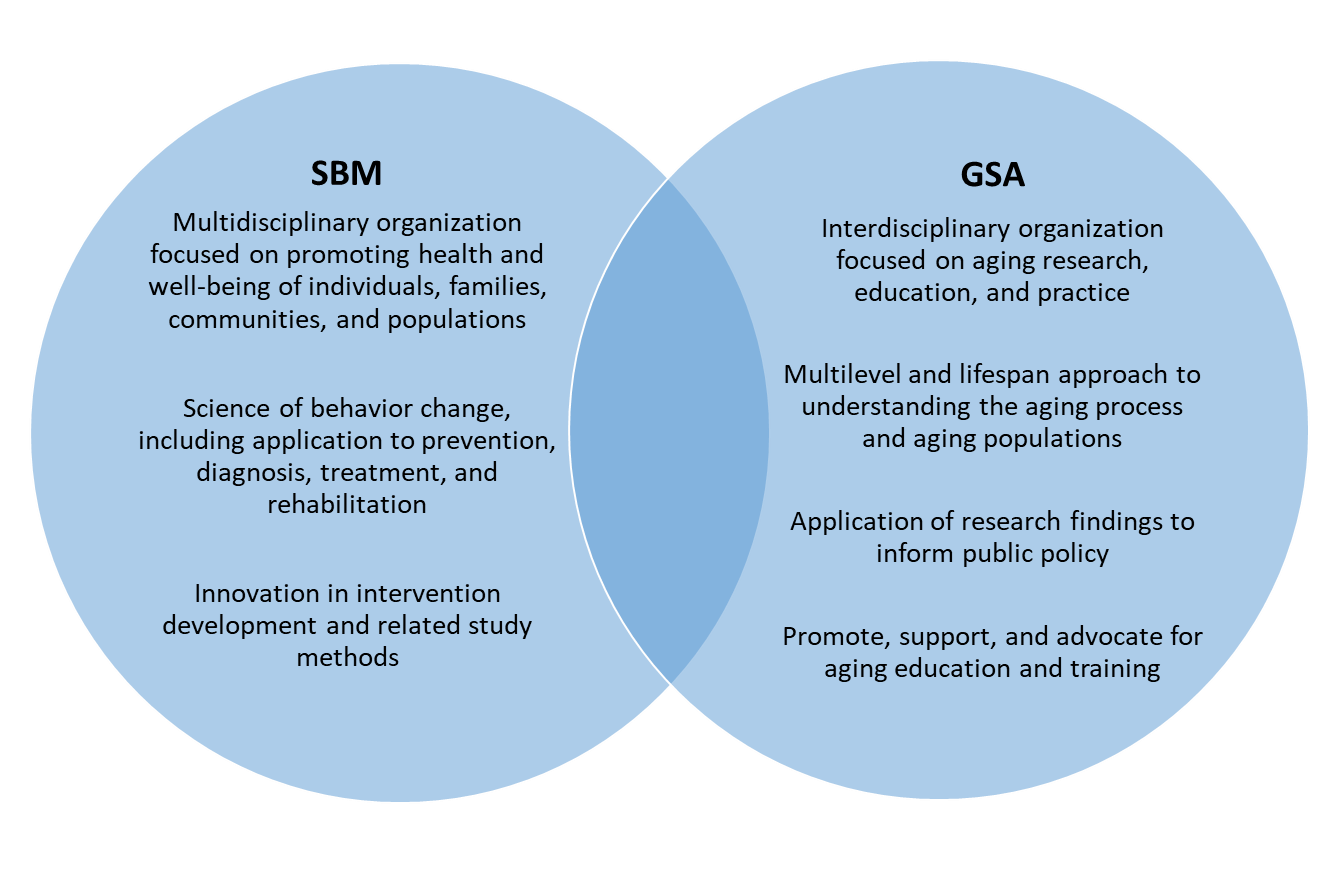

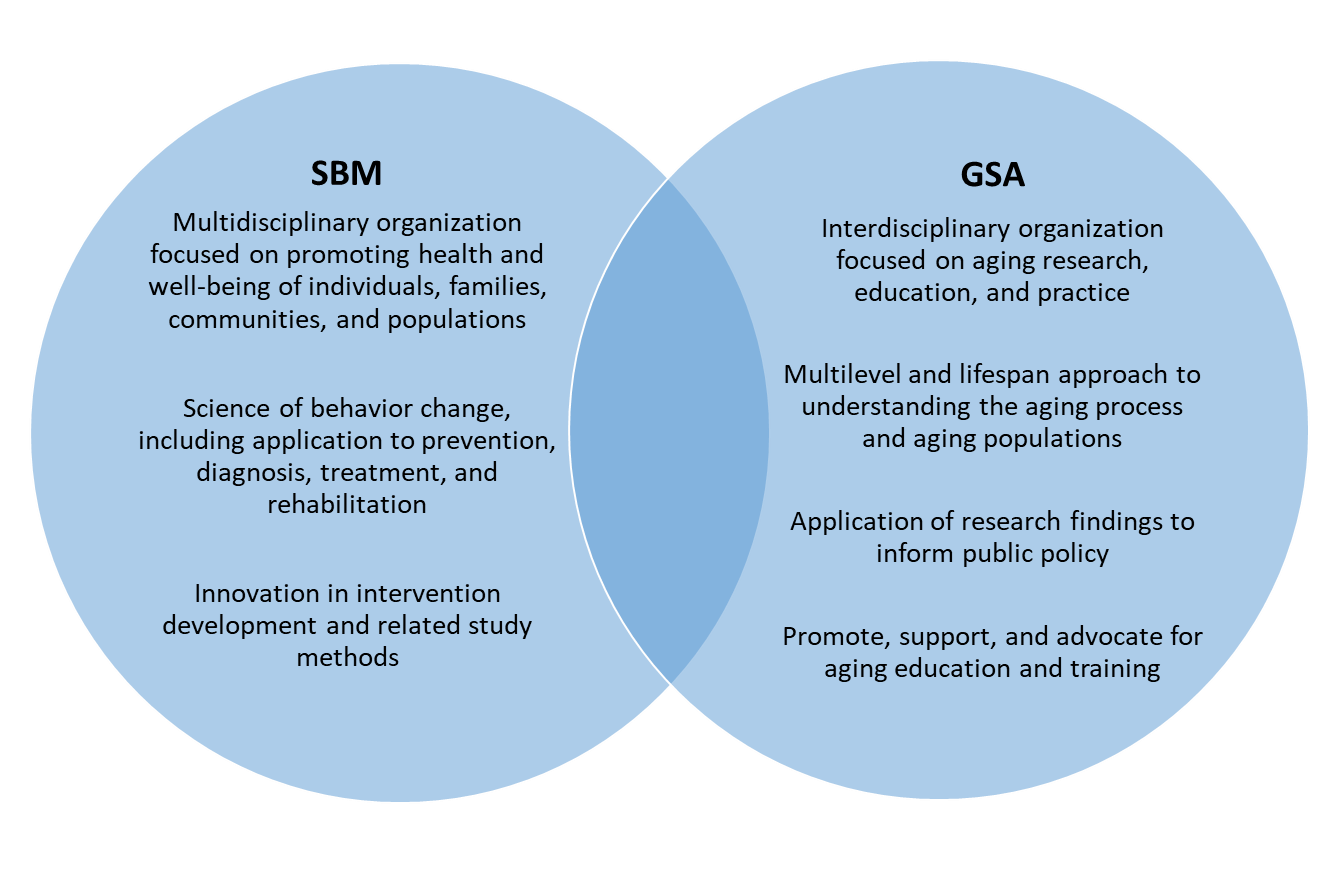

The Society for Behavioral Medicine (SBM) Aging Special Interest Group (SIG) is focused on addressing the unique issues of behavior change among older adults, including the influence of psychosocial, cultural, environmental, and policy factors that are particular to aging and late life. In order to advance behavioral medicine knowledge and practice that has high impact for older adults’ health, the Aging SIG has begun exploring ways in which SBM may foster collaboration with the Gerontological Society of America (GSA), a premier organizational leader in the promotion of multi- and interdisciplinary research, knowledge dissemination, and education in gerontology and aging. We suggest that the scientific and societal impact of this collaboration will come not only from the overlapping interests in ensuring the health and well-being of older adults, but the unique foci and expertise that each organization brings.

Toward this end, we have been collaborating on this initiative with long time Aging SIG member, Dr. Barbara Resnick. Dr. Resnick’s imminent gerontology and aging research and vast experience in societal leadership, serving as president of both GSA and the American Geriatrics Society, a founder and leader of the Aging SIG, and former SBM SIG Council Chair, make her well-poised to help advance collaborations between SBM and GSA. We asked Dr. Resnick to share her thoughts and vision for how our societies can work together to foster shared missions.

What is the history of collaborations between GSA and SBM?

For many years, SBM and GSA have each had members from both societies who have participated in the other organization’s annual meeting. A formal relationship was explored several years ago, initiated by the work of Dr. Sherri Sheinfeld Gorin, in her former role as Scientific and Professional Liaison Council Chair. This exploration was based on interest on the part of both organizations to expand the critically important focus on aging in SBM, and, in GSA, the methods and activities related to behavior change.

When, and how, did collaboration between the two organizations start? What type of conversations and activities has this partnership resulted in?

Conversations were initiated between leadership from both organizations to see what types of activities could be done that would be advantageous to both organizations. One of our first goals was the development of a Policy Brief through GSA that addressed the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit. This was completed and published and disseminated through GSA and SBM channels. We have continued to discuss opportunities including such things as joint symposia at GSA and SBM annual meetings, informal Meet and Greet sessions, and webinars throughout the calendar year. We also decided to share things like conference information and webinar options, as well as other resources from each organization. This information sharing is a good launching point at this time to reinvigorate this collaboration. GSA Connect, SBM Outlook, and SIG listservs can all serve as platforms for ongoing information sharing. A primary short-term goal should be to increase awareness of each society, particularly to potential members who do not currently belong to both organizations.

What do you believe are some potential benefits of partnering/collaborations between both of these professional organizations?

A major benefit of partnering is increasing opportunities for members from either organization to learn more about the other organization, and hopefully join and expand their knowledge in the areas specific to both groups. GSA brings to the table a focus on gerontological, geriatric, and aging-related research, policy, and practice. SBM covers the full lifespan but has a primary focus on the science of behavior change, including a multitude of behaviors and methods around behavior change. There is crossover and learning to be had on both sides.

Who are some of the key stakeholders in each organization who can assist with developing the collaboration?

Initially, the partnership should be supported by the executive directors of the organizations and the boards. There are no cost implications, generally, and thus it is a win-win for both groups.

How can these two groups collaborate in the future?

A good path is continued work aimed at sharing opportunities within each organization to the others’ members, and enticing new membership across the groups. In 2019, the SBM Aging SIG hosted an affiliate event at the GSA Annual Meeting to showcase the research being conducted by investigators who are members of both organizations. This is a good way to get the word out to GSA members who may be conducting behavioral medicine research with older adults, but are not aware of the scientific collaboration and networking benefits available with SBM membership. Similar events could be integrated into the SBM Annual Meeting to share the benefits of GSA membership with SBM researchers whose work naturally involves older adults.

I would say that the biggest barrier raised by all in terms of interest is the cost for multiple memberships. Future work might focus on developing a combined membership or reduced membership cost for one if you belong to the other, or reduced conference fees for members of the other organization. In general, strategic planning that can optimize the value of membership for all can greatly benefit both organizations.

What advice do you have for other SIGs who might be interested in collaborating with another scientific society or professional organization?

Begin with information sharing and other low-hanging fruit, like collaborative webinars and symposia that can be advertised jointly. I think that this process of information sharing and collaborative activities works well. It is not burdensome in any way. It is difficult to really evaluate the outcomes for SBM and GSA at this time, but I believe it has raised some awareness across the organizations that the other one exists.

For more information about the Gerontological Society of America, please go to: https://www.geron.org/

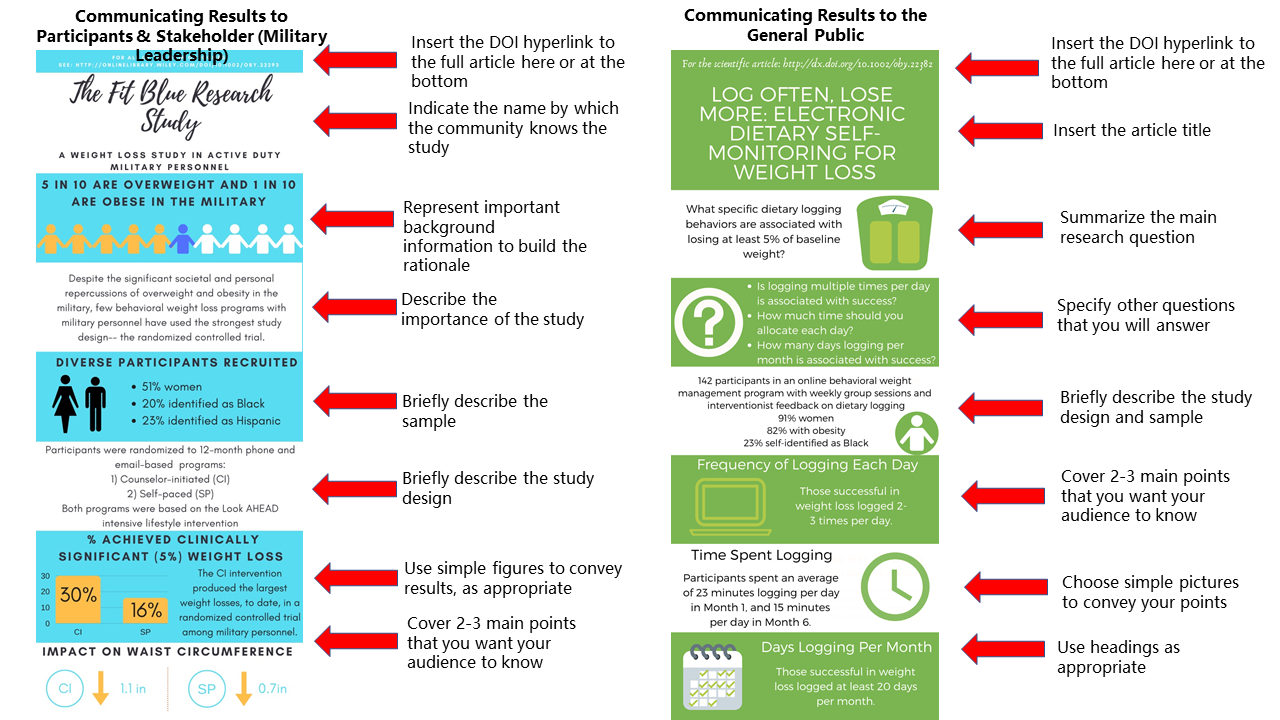

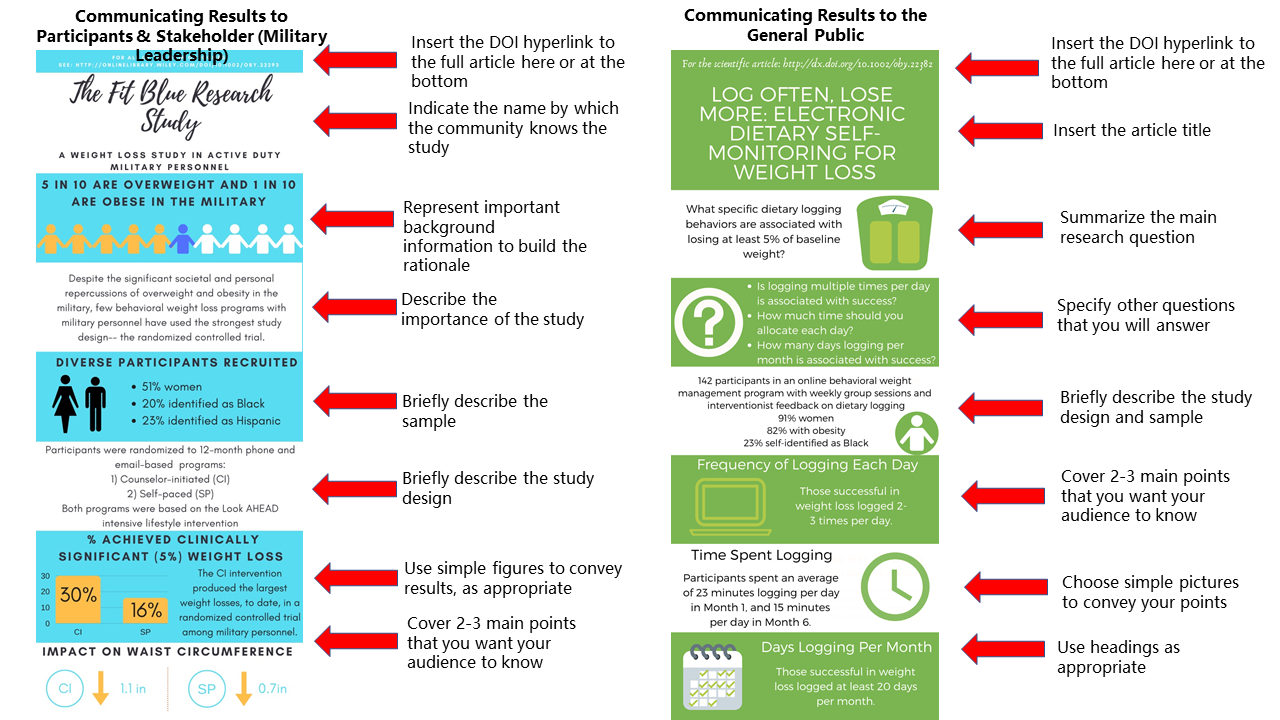

Using Infographics to Convey Research Findings

Becca Krukowski, PhD✉ and Carly M. Goldstein, PhD✉; Civic and Public Engagement Committee

Infographics are an effective tool for science communication and dissemination. Blending text and graphics, infographics can help you communicate scientific findings to the public, other scientists, and patient communities. Since they are easier to read and require less prerequisite scientific knowledge to understand than a research paper, they can increase access to scientific findings. If you are considering creating and sharing an infographic summarizing some of your recent work, consider these do’s and don’ts as you get started:

Do: Find a design tool that works for you. Ideally, a design tool would have templates to inspire your creativity, simple pictures to use, and tools to help you precisely align the components in your infographic. We personally use the free version of Canva.

Don’t: Try to fit your whole research article into an infographic. The essential points to cover are conveying the research question and 2-3 most important results (specific to what your audience cares about). Aim for 150 words or fewer.

Do: Consider your audience. Infographics can be used to convey information to research participants, politicians, other stakeholders, the general public, or scientific audiences. Tailor your infographic to the audience. One paper may warrant multiple infographics communicating different information to different groups.

Don’t: Be intimidated by infographics. With the help of a design tool, an infographic can be drafted in an hour or two. You will then want to get feedback on the infographic from your scientific colleagues and also friends and relatives who are not as familiar with your research.

Do: Make your infographic pleasing to the eyes. Choose colors carefully to make sure that your infographic will be easily readable and that the colors work together well.

Don’t: Follow these guidelines 100%. These guidelines will hopefully help you get started with making infographics by revealing some “formulas” that can be used. But as long as your infographic is clearly communicating your research to your intended audience, you are doing it correctly!

Do: Distribute your infographic widely. While most journals do not (yet!) encourage or support submitting an infographic alongside your scientific article, sharing your infographic on social media is a great way to disseminate your research to multiple audiences. Consider what hashtags you may want to use on social media or consider sending your infographic directly to patient-facing organizations that can send it to their membership.

Next time you publish a paper, consider creating an accompanying infographic targeting communication with lay audiences to increase the public health impact of your work. When you share an infographic on Twitter, tag @BehavioralMed, and let the SBM community amplify your efforts!

Mental and Social Health in Musculoskeletal Specialty Care: An Interview with Dr. David Ring

Emily Walsh✉; Samantha Farris, PhD✉; Ana-Maria Vranceanu, PhD✉; Pain SIG

David Ring, MD, PhD

The Pain Special Interest Group (Pain SIG) recently interviewed Dr. David Ring, Associate Dean for Comprehensive Care and Professor of Surgery and Psychiatry at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin about his perspectives on addressing mental and social health in musculoskeletal specialty care.

You’re involved with a project investigating the role of a mind-body program in the acute orthopedic trauma setting. Can you tell us about the novelty of this intervention?

My long-time psychology collaborator, Dr. Ana-Maria Vranceanu put together a team was awarded a U01 from NCCIH to do a multicenter, multi-year investigation expanding on work we did to develop and test the “Toolkit for Optimal recovery after injury”, a 4-session live video program aimed at optimizing recovery and preventing transition to persistent pain and disability. We’ve known for a long time that psychosocial factors such as anxiety about pain and catastrophic thinking about pain at the time of the injury are associated with persistent pain and disability months after the injury. The Toolkit is the first program design specifically for the 20-50% individuals who endorse high levels of catastrophic thinking or pain anxiety. We have done some preliminary work in the Orthopedic Trauma at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and showed the program is feasible and associated with improvement in pain, disability, depression and post-traumatic stress. We now have the opportunity to evaluate the program at 2 additional level 1 trauma centers, Kentucky Medical Center and Dell Medical Center.